In the world of industrial machinery and hydraulic systems, efficiency and reliability aren’t just goals—they’re necessities. Whether you’re operating heavy construction equipment, managing manufacturing processes, or maintaining mobile hydraulic machinery, one component plays a crucial role in ensuring smooth, consistent performance: the hydraulic accumulator. This often-overlooked device acts as the safety net and power reserve that keeps hydraulic systems running optimally, even under demanding conditions.

Understanding hydraulic accumulators is essential for engineers, maintenance professionals, and anyone working with hydraulic equipment. In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what hydraulic accumulators are, why they’re indispensable in modern hydraulic systems, and how different types serve various industrial applications.

What Is a Hydraulic Accumulator?

A hydraulic accumulator is a pressure storage device that stores hydraulic energy in the form of pressurized fluid. Think of it as a rechargeable battery for hydraulic systems instead of storing electrical energy, it stores potential energy by compressing a gas (typically nitrogen) or a spring mechanism against hydraulic fluid.

A hydraulic accumulator is a pressure storage device that stores hydraulic energy in the form of pressurized fluid. Think of it as a rechargeable battery for hydraulic systems instead of storing electrical energy, it stores potential energy by compressing a gas (typically nitrogen) or a spring mechanism against hydraulic fluid.

In a hydraulic circuit, the accumulator serves as an auxiliary component that can quickly release stored energy when the system demands extra power or absorb excess fluid when pressure spikes occur. The basic working principle involves a separation between hydraulic fluid and a compressible medium (gas or mechanical spring). When the hydraulic pump generates pressure, fluid enters the accumulator and compresses the gas or spring. This stored energy can then be released instantly when needed, providing supplemental flow without requiring the pump to work harder.

This simple yet ingenious design makes hydraulic accumulators invaluable across countless applications, from smoothing out pressure fluctuations to providing emergency backup power when primary pumps fail.

Purpose of a Hydraulic Accumulator

The hydraulic accumulator purpose extends far beyond simple energy storage. These versatile devices fulfill multiple critical roles that enhance system performance, safety, and longevity:

- Energy Storage for Peak-Demand Moments: Hydraulic systems often experience cyclical operations where power demands fluctuate dramatically. Rather than sizing pumps for maximum peak demand which would result in oversized, inefficient equipment running at partial capacity most of the time, accumulators store energy during low-demand periods and release it during peak requirements. This allows for smaller, more efficient pumps while still meeting peak power needs.

- Shock Absorption and Pressure Spike Reduction: Sudden valve closures, rapid cylinder stops, or water hammer effects can create destructive pressure spikes that damage components and reduce system life. Accumulators act as cushioning devices, absorbing these shocks by allowing fluid to temporarily compress the gas chamber. This protective function extends the lifespan of pumps, valves, seals, and other sensitive components.

- Emergency Power Supply During Pump Failure: Safety-critical applications require backup power sources. When a pump fails or power is interrupted, a properly sized accumulator can provide emergency hydraulic pressure to complete essential operations—like lowering a load safely, engaging brakes, or retracting critical components to a safe position.

- Leakage Compensation and Pressure Maintenance: All hydraulic systems experience minor internal leakage. In applications requiring sustained pressure over extended periods without pump operation, accumulators compensate for this gradual fluid loss, maintaining system pressure and preventing performance degradation.

- Thermal Expansion Compensation: Temperature variations cause hydraulic fluid to expand and contract. In closed systems, this volume change can create excessive pressure or vacuum conditions. Accumulators accommodate these thermal variations, protecting the system from temperature-induced damage.

Understanding the purpose of hydraulic accumulators reveals why they’re considered essential rather than optional in most modern hydraulic systems.

Function of a Hydraulic Accumulator

The function of a hydraulic accumulator centers on its ability to store and release hydraulic energy in precise synchronization with system demands. But how exactly does this process work in real-time operation?

The Charging and Discharging Cycle

When the hydraulic pump operates and system demand is low, excess hydraulic fluid flows into the accumulator. This fluid compresses the gas (or spring) on the other side of the separating element, storing potential energy. The pre-charge pressure—the initial gas pressure before any fluid enters—determines when the accumulator begins accepting fluid and how much energy it can store.

During the discharging phase, when system demand exceeds pump capacity or the pump stops, the compressed gas expands, pushing hydraulic fluid back into the system. This process happens almost instantaneously, providing supplemental flow exactly when needed.

Interaction Between Components

The effectiveness of this energy transfer depends on the separation mechanism between the hydraulic fluid and compressible medium. Whether using a bladder, piston, or diaphragm (which we’ll explore in detail shortly), the separator must maintain complete fluid isolation while allowing efficient energy transfer. The gas side (typically nitrogen due to its inert properties and resistance to combustion) provides the compressible medium that stores energy through compression.

The 3 Types of Hydraulic Accumulators

While hydraulic accumulators all serve the same fundamental purpose, they achieve it through different mechanical designs. The three types of hydraulic accumulators most widely recognized and used in industry are bladder, piston, and diaphragm accumulators. Each type offers distinct advantages suited to specific applications and operating conditions.

Bladder Accumulators

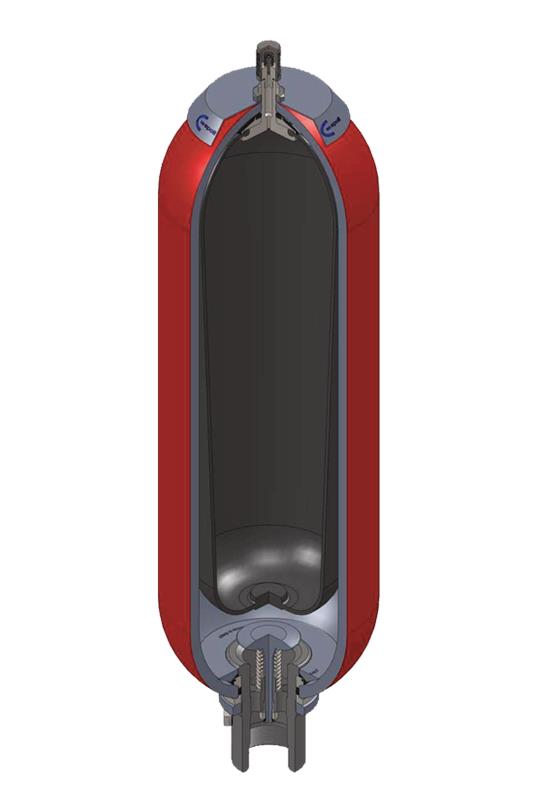

- Structure and Design: Bladder accumulators feature a flexible elastomeric bladder contained within a metal shell. The bladder is filled with compressed nitrogen gas and occupies the entire internal volume when the accumulator is uncharged. As hydraulic fluid enters through a port at the bottom, it compresses the gas-filled bladder upward. A poppet valve at the fluid port prevents the bladder from extruding through the opening when fully discharged.

- Working Principle: The bladder creates a complete barrier between the hydraulic fluid and nitrogen gas. During charging, incoming fluid squeezes the bladder, compressing the gas and storing energy. During discharge, the compressed gas expands, forcing the bladder to push fluid back into the system. The flexible nature of the bladder allows for rapid response to pressure changes.

- Advantages: Bladder accumulators excel in applications requiring fast response times and effective shock absorption. They provide excellent separation between gas and fluid, minimizing gas absorption into the hydraulic oil. Their relatively lightweight design makes them ideal for mobile applications. Maintenance is straightforward, as bladders can be replaced without specialized equipment in most designs.

- Common Applications: These accumulators dominate in construction machinery (excavators, loaders, backhoes), mobile equipment, automotive suspensions, and any application where weight, response speed, and shock absorption are priorities. They’re particularly effective in systems with moderate pressure ranges (up to approximately 5,000 PSI) and where space constraints favor compact designs.

Piston Accumulators

- Structure and Design: Piston accumulators use a sliding piston to separate the gas and fluid chambers within a cylindrical pressure vessel. The piston moves freely within the bore, with seals preventing cross-contamination between the gas and fluid sides. Some designs feature a piston rod extending through one end cap, while others use free-floating pistons.

- Working Principle; As hydraulic fluid enters the accumulator, it pushes the piston, compressing the gas on the opposite side. The piston’s movement is linear and predictable, allowing for precise calculations of stored energy and available fluid volume. The mechanical separation provides complete isolation between gas and fluid throughout the pressure range.

- Advantages: Piston accumulators handle higher pressure ranges than other types often exceeding 10,000 PSI—making them suitable for demanding industrial applications. They’re available in larger volumes and can be customized in length and diameter to fit specific space requirements. The robust construction and simple design result in long service life and reliability. They also tolerate wider temperature ranges and more severe operating conditions than bladder or diaphragm types.

- Applications: Industrial hydraulic presses, heavy-duty manufacturing systems, offshore oil and gas equipment, large injection molding machines, and any stationary application requiring high pressure, large volume, or extreme operating conditions typically employ piston accumulators. Their durability makes them the preferred choice when reliability and maintenance intervals are critical considerations.

Diaphragm Accumulators

- Structure and Design: Diaphragm accumulators utilize a flexible diaphragm (either welded or clamped between two halves of the accumulator body) to separate gas and fluid. The diaphragm is typically made from elastomeric materials suitable for the operating fluid and temperature range. The design is inherently compact, with minimal internal volume dedicated to structural components.

- Working Principle: The diaphragm flexes in response to pressure differences between the gas and fluid sides. When fluid enters, the diaphragm deflects toward the gas side, compressing the nitrogen. When fluid is needed, the compressed gas pushes the diaphragm back, expelling fluid into the system. The flexing action accommodates pressure changes while maintaining complete separation.

- Advantages: Diaphragm accumulators offer the most compact design of the three main types, making them ideal for space-constrained applications. They’re generally the most economical option, particularly in smaller sizes. The simple construction with fewer moving parts enhances reliability and reduces maintenance requirements. They respond quickly to pressure changes and work well in applications with frequent cycling.

- Applications: These accumulators are commonly found in light equipment, automotive brake systems, lubrication systems, small mobile machinery, and applications where cost, space, and moderate pressure requirements (typically under 3,000 PSI) are primary considerations. They’re excellent choices for pulsation dampening and maintaining pressure in auxiliary circuits.

How to Choose the Right Hydraulic Accumulator

Selecting the appropriate accumulator type and size requires careful consideration of multiple factors:

- Application Requirements: Begin by clearly defining what you need the accumulator to do. Is it primarily for shock absorption, energy storage, emergency backup, or maintaining pressure? Different applications favor different accumulator types. Mobile equipment typically benefits from bladder accumulators, while stationary industrial systems often perform better with piston types.

- Pressure Ratings: Match the accumulator’s pressure rating to your system’s maximum working pressure with appropriate safety margins. Diaphragm accumulators suit lower-pressure systems (under 3,000 PSI), bladder accumulators handle moderate pressures (up to 5,000 PSI), and piston accumulators excel in high-pressure applications (5,000 PSI and above).

- Volume and Capacity: Calculate the required fluid volume based on your specific application. Energy storage applications need larger volumes, while shock absorption may require less. Consider both the total accumulator volume and the usable fluid volume between maximum and minimum working pressures.

- Response Speed: Applications requiring rapid response (shock absorption, fast cycling) favor bladder and diaphragm accumulators due to their lightweight separating elements. Piston accumulators, while slightly slower, still provide excellent response in most applications.

- Cost and Maintenance Considerations: Balance initial cost against long-term maintenance requirements and expected service life. Diaphragm accumulators offer the lowest initial cost but may require more frequent replacement in demanding applications. Piston accumulators cost more initially but typically provide longer service intervals in harsh environments.

Common Applications Across Industries

Hydraulic accumulators serve diverse industries, each leveraging their unique capabilities:

- Construction Equipment: Excavators, loaders, and cranes use accumulators to provide instantaneous power for boom movements, smooth operations, and absorb shocks from ground impacts and sudden load changes.

- Oil & Gas Machinery: Drilling equipment, blowout preventers, and subsea control systems rely on accumulators for emergency backup power and maintaining critical safety functions in remote, unmanned operations.

- Industrial Manufacturing Systems: Injection molding machines, metal stamping presses, and automated assembly lines use accumulators to provide consistent pressure during forming operations and reduce cycle times by supplementing pump flow during peak demands.

- Agricultural Machinery: Tractors, harvesters, and other farm equipment employ accumulators for suspension systems, implement control, and providing smooth, responsive operation across varied terrain.

- Automotive Brake Systems: Modern vehicles use accumulators in anti-lock braking systems (ABS) and hybrid brake systems to ensure immediate brake pressure availability and smooth brake pedal feel.

Pros and Cons of Hydraulic Accumulators

Benefits

Hydraulic accumulators enhance system efficiency by reducing pump size requirements and minimizing energy consumption. They provide excellent shock control, protecting expensive components from damaging pressure spikes. Energy savings result from allowing pumps to operate at consistent speeds rather than cycling on and off. They improve response times by providing instantaneous supplemental flow and enable emergency shutdown procedures when primary power fails.

Limitations

All accumulator types can experience gas leakage over time, requiring periodic pre-charge pressure checks and maintenance. Bladders and diaphragms have finite service lives and need replacement after extensive cycling or aging. Pressure constraints mean each type has maximum operating limits. Proper sizing requires careful calculation—undersized accumulators won’t meet system needs, while oversized units waste money and space. Temperature extremes can affect gas pressure and elastomer properties, potentially reducing performance in extreme environments.

Maintenance Tips for Longer Accumulator Life

Proper maintenance extends accumulator service life and ensures reliable performance:

Pre-Charge Pressure Checks

Verify gas pre-charge pressure quarterly or according to manufacturer recommendations. Incorrect pre-charge pressure dramatically reduces accumulator effectiveness. Check when the accumulator is fully depressurized and isolated from the system.

Inspection of Separating Elements

Monitor for signs of bladder, piston, or diaphragm wear. Fluid appearing in the gas charge port indicates separator failure requiring immediate replacement. Listen for unusual noises that might indicate internal component failure.

Temperature and Pressure Cycle Monitoring

Track operating temperatures and pressure cycles. Excessive heat accelerates elastomer degradation, while pressure cycling beyond design limits shortens service life. Install pressure gauges and temperature sensors where practical.

Cleaning and Contamination Control

Maintain clean hydraulic fluid according to system specifications. Contamination accelerates seal and separator wear. Use appropriate filtration and follow recommended fluid change intervals.

Regular Inspections

Visually inspect accumulator shells for corrosion, dents, or damage. Check mounting hardware and connections for tightness and signs of leakage. Document inspection findings and maintain service records to track trends and predict maintenance needs.

Conclusion

Hydraulic accumulators represent a critical technology that enhances the performance, efficiency, and reliability of hydraulic systems across countless industrial applications. From their fundamental purpose of storing hydraulic energy to their sophisticated functions in managing pressure, providing emergency power, and protecting expensive components, these devices prove their worth every day in equipment worldwide.

Understanding the three types of hydraulic accumulators—bladder, piston, and diaphragm—enables you to select the right solution for your specific application. Whether you need the fast response of a bladder accumulator for mobile equipment, the high-pressure capacity of a piston accumulator for heavy industrial systems, or the compact economy of a diaphragm accumulator for lighter applications, there’s an accumulator type engineered for your needs.

Selecting the right hydraulic accumulator and maintaining it properly ensures safe, efficient hydraulic performance that maximizes equipment uptime and minimizes operational costs. As hydraulic technology continues advancing, accumulators remain indispensable components that bridge the gap between steady pump operation and variable system demands.

FAQs :

1. What is a hydraulic accumulator?

A hydraulic accumulator is a pressure storage device that stores energy in the form of pressurized fluid to stabilize system pressure, absorb shocks, and improve efficiency.

2. Types of accumulators in a hydraulic system?

The main types are bladder, diaphragm, piston, and spring-type accumulators, each designed for different pressure, speed, and volume requirements.

3. How does an accumulator work in a hydraulic system?

An accumulator stores hydraulic fluid under pressure using a compressible medium like gas or a spring, then releases it when the system needs extra force or pressure stabilization.

4. How to tell if a hydraulic accumulator is bad?

The most common indicator is pressure instability within the system. This includes unexplained pressure drops, inability to maintain consistent pressure, or pressure spikes during operation all suggesting the accumulator is no longer effectively storing energy or dampening pressure fluctuations.

5. what is the primary function of an accumulator?

The primary function of an accumulator is to store energy, whether in a hydraulic system to maintain pressure or in a CPU for computational tasks. In hydraulic systems, this involves storing pressurized fluid to act as a power reserve for emergencies, to smooth out pressure pulses, and to supplement pump flow